Becoming a Radical Black Woman: What Women Behind MLK Taught Us

Martin Luther King, Jr. missed an opportunity to be truly revolutionary by allowing his men to put themselves before the Black women working just as hard for the rights of all Black people.

As a result, the Black women behind his movement strategized around defending themselves. Their distant cousins across the Atlantic, feeling equally trivialized by the men in their communities, did the same.

The radical feminist approaches forged by them aren’t taught or used enough by Black women today, partially because there aren’t national holidays giving us the paid time off to reflect on the women who formed them.

Kimberle Crenshaw coined the phrase “intersectionality” 25 years after he died, but there’s no way MLK—a civil rights leader during a post-World War, anti-colonial and Pan-Africanist world— didn’t know that being Black and a woman made someone uniquely vulnerable to injustice.

He oversimplified the idea in his speech on Washington, suggesting “Black girls” join “white girls as sisters” to solve the problem. He unpacked it some more in Letter from Birmingham Jail:

“All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality…I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be…This is the inter-related structure of reality.”

The Black women who stood with and came after King provided the blueprint to execute this dream. It’s only right that we celebrate them as much as we celebrate MLK Day today. Here’s a lesson on being a radical Black woman, collaborating effectively with Black women across the African diaspora to live better lives.

Images of Black Women in Media

Journalist Ethel L. Payne interviewing a Black soldier.

After giving a little-known preacher from Atlanta his first news break, Ethel L. Payne, like other women organizers behind MLK and his male colleagues, fought to make sure Black women were seen and seen well.

Ethel became the most influential Black woman in American news media starting with her spotlight on racism and anti-miscegenation in the Korean War. She used her status at the Chicago Defender, the largest and most-read Black-owned newspaper worldwide at the time, to publish humanizing stories about Black women, rallying for mutual aid on their behalf.

She exposed the discriminative pattern of Black children taken from poor single Black mothers and placed in foster care. The number of Black families adopting Black children spiked in the 1950s because of her reporting. As the first Black woman member of the White House press corps, she used her access to grill presidents on their promises to protect Black citizens, facing microaggressions and IRS audits from the Press Secretary to intimidate and discredit her. She even took her talents abroad, becoming close with Winnie Mandela and documenting her and her husband’s anti-apartheid fight in South Africa.

Black women tweeting with the hashtag #softlife and making viral videos about rest over labor is understandable. It’s a natural reaction to feeling stretched thin by responsibilities to their communities. But as exhausting as it is to be the strong Black woman, Ethel shows us how invaluable an asset Black women’s tenacity can be.

The Black women that followed Ethel (like April Ryan) probably wouldn’t dare to ask “impertinent questions” in coveted spaces without Ethel sacrificing comfort to challenge conformity. Her choice to not marry or start a family due to the demands of her work doesn’t mean every Black woman has to give up personal desires to achieve the same. It’ll be wise, though, to remember not to lose our voice in service to ourselves. A seat at the highest tables is a chance to air out complaints where racist systems would otherwise want us complicit.

Black Women Economics

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (far right), with market women in Abeokuta, Nigeria.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and Charlene Mitchell were 6,000 miles and 30 years apart from one another. But they had this in common: knowing that education plus unionization produced the fastest political and financial ROI for Black women.

Funmilayo founded the Abeokuta Ladies Club (ALC), which later became the Federation of Nigerian Women’s Societies (FNWS). One of the organization’s biggest achievements was ending unfair taxes on businesswomen’s profits. Her success most likely came from quickly realizing the initial elitism of the ALC, and inviting undereducated market women to join as members.

Today, the business conference circuit touts its ability to help Black women entrepreneurs “level up.” But pricey event tickets and branding targeting a certain demographic (i.e. college-educated Black women) while isolating another (low-income, working-class Black women) stop these events from delivering the radical results the ALC produced without goodie bags or corporate sponsors.

The protests Funmilayo and the ALC inspired forced one of the most powerful men in Nigeria, the Alake of Abeokuta, to step down. Despite being funded directly by the British colonialists to guard their business interests, the Alake relented under the pressure of 10,000 women refusing to be exploited.

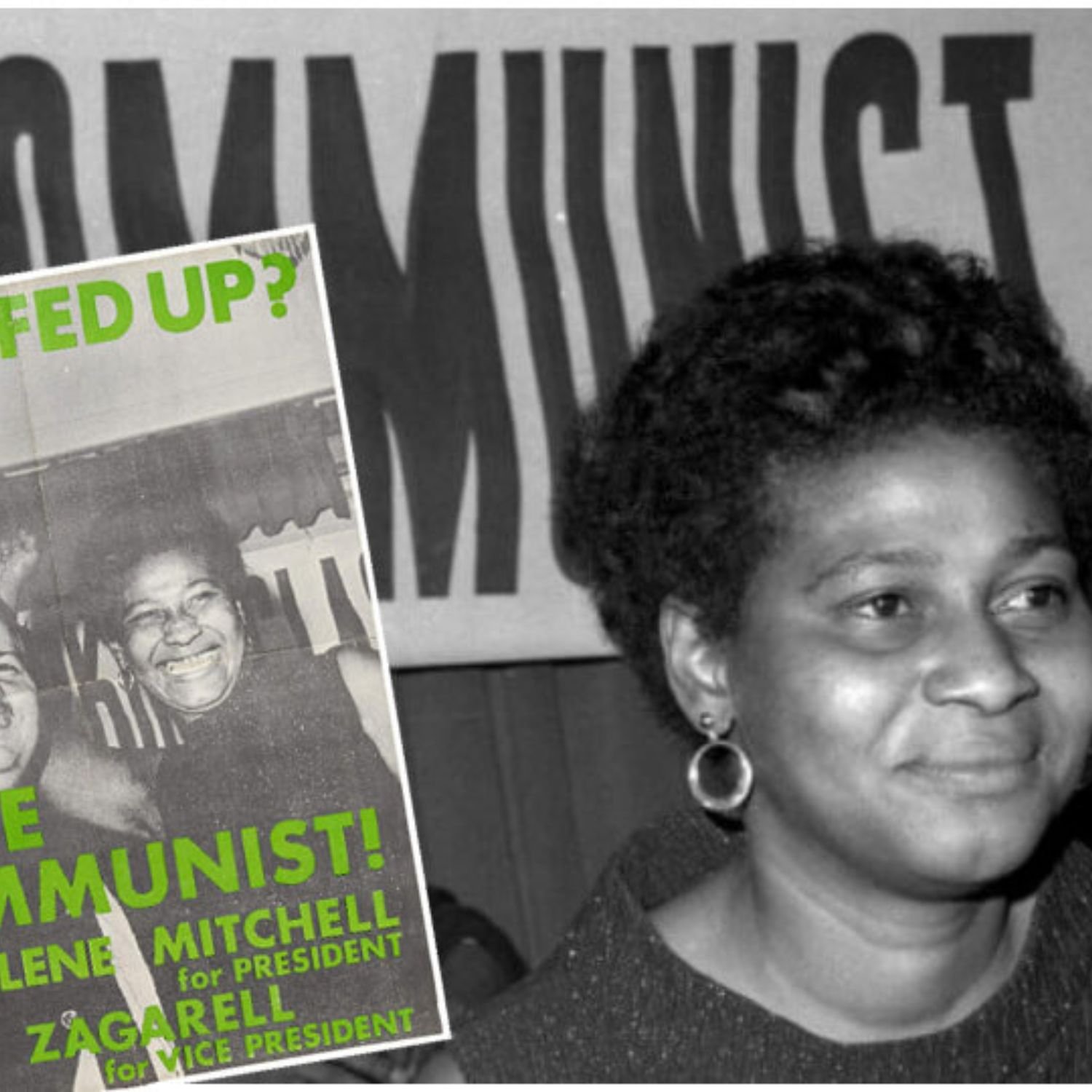

Charlene Mitchell at a presidential campaign event.

Charlene Mitchell, equally inspired by her family’s politics and radicalism across the diaspora, joined the Communist Party at 16. Her whole life, which ended in December 2022 at age 92, involved community organizing under socialist principles. In her words, “replacing white capitalism with black capitalism isn't going to solve the problems of poverty: the problems of poverty are rooted in the nature of capitalism itself."

Charlene’s political actions included getting Angela Davis’ out of jail when showing Angela support branded her as an enemy of the state. She’s also the first Black woman to run for U.S. president, doing so under the Communist Party and campaigning for anti-discriminatory housing and labor laws. Her civic action also included simpler things, like hosting lectures on street corners or helping friends manage their small shops when they needed a break.

Charlene Mitchell is an example of combining humility and sisterhood with ambition. It’s offensive that Charlene’s contribution to American history isn’t taught in schools or well-known. Thankfully, she put service to the greater good over fame, though she deserves far more recognition for paving the way for her proteges Shirley Chisholm and Kamala Harris.

Black Women Saving Lives

Harriet Tubman once said, “there was one of two things I had a right to: liberty, or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other; for no man should take me alive.”

Sadly, that’s the ultimatum presented to Black women when they speak out against misogynoir. Before celebrity stories like Meg thee Stallion’s or Rihanna’s, Black women received literal death threats for bringing charges against their abusers. From slavery until today, Black women have been targets of physical and sexual violence by domestic partners and white supremacists protected under racist patriarchal systems. An accurate account of the number of Black women lynched in the 1950s and 1960s still doesn’t exist.

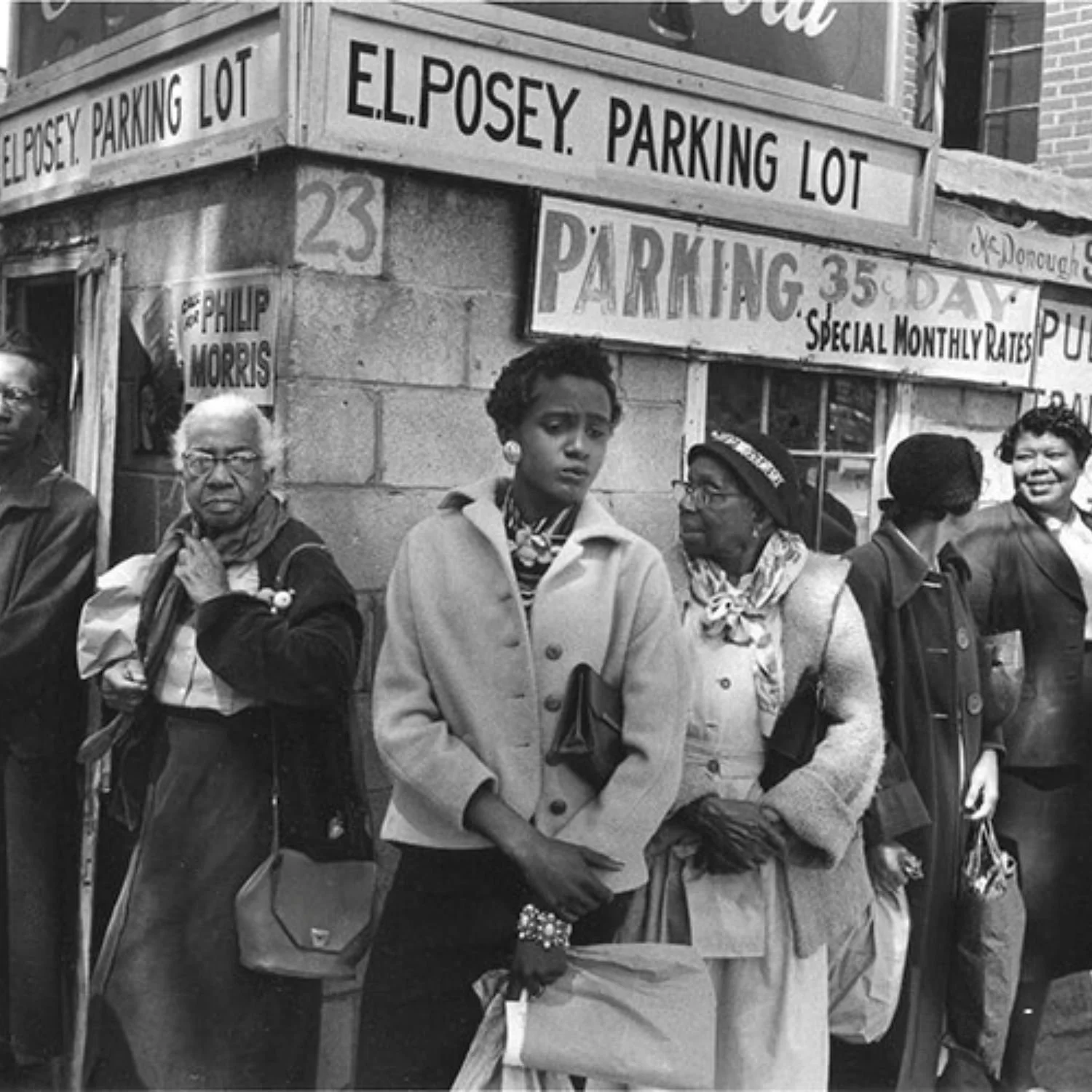

Black women in Montgomery, AL during the bus boycott.

In this environment, Black women provided each other with refuge in informal and formal ways. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott (sparked by a Black woman, Rosa Parks), Black women traveled in packs to protect each other against harassment or violent attacks. Socialist leaders like Claudia Jones of the Civil Rights Congress fought for the adjudication of white men who assaulted Black women and to acquit Black women like Rosa Lee Ingram who retaliated in self-defense.

Photo of Claudia Jones of the Civil Rights Congress (CRC).

The Brixton Black Women’s Group, a socialist feminist community in London, was founded on the teachings of Black Americans like bell hooks and Patricia Hill Collins. This group is both an inspiration and a warning about Black women who believe they’re practicing intersectionality. The group united multiple diasporic ethnicities to end violence against Black women, which was no easy feat back then. But some members undermined the concerns of non-heteronormative Black women by calling them “private” issues “too sensitive” to debate.

Two common threads wove threw these stories about male-dominated civil rights organizations and Black women starting their own: one, the refusal of most men to be unequivocal allies to Black women; two, infighting between women with different views on who deserved protection under the label of “woman.”

Schools, universities, and books taught us many lessons about MLK 37 years since the U.S. gave him a holiday. The most important still eludes us, and that’s team building. MLK might have been the face of a movement, but he died before producing a coalition. Remarkable women laid the foundation for one. It’s up to us to examine closely the type of bricks to continue layering on this framework, that won’t buckle under the vices that kept our predecessors from finishing the job.